Life in Mucus

February 26, 2013

February 26, 2013

Monday was a busy day for flatworms and nudibranches. The water was cold, and the currents were mild. There were probably some other invisible elements that drew all the crawlies out from their hiding places to openly traverse the sea bed and coral reef. For some reason, the tens of seahorses that were sighted just the day before had disappeared into hiding. I wished I’d gotten the memo.

One of the fascinating things about the marine flatworms at Pulau Hantu is how large they can get. The individual in the photo above was larger than my palm. Some species of flatworms are known to grow up till 24 inches, and the smallest are just 1mm in length! I wonder if there is a terminal size for flatworms, or if they could, they would just keep growing.

They may not look like it, but flatworms are carnivores. They feed on other small worms, and plankton, and also on things on the reef like ascidians, bryozoans and other small invertebrates. Perhaps flatworms have easy access to these sorts of organisms in Singapore reefs, allowing them to get large so quickly. It is believed that marine flatworms have a lifespan of about two years. I had long thought that flatworms began life as plankton, but I recently learned that mini adults hatch from the eggs. This probably gives them a real head start to begin feeding and growing as quick as possible. Despite their simple physiology, these flatworms also move very fast.

The skin of flatworms is covered with tiny mobile hairs called cilia. When these hairs move, it helps to propel the flatworm. Just below its skin, a flatworm has many glands embedded between its muscle layers. These glands secrete mucous or adhesives that assist the flatworm in crossing different types of terrain. Some species are also able to swim by undulating their marginal ruffling.

Flatworms have very simple eyes that only detect motion and shadows. Some flatworms are believed to have some kind of pressure sensor in their “heads” so they don’t actually see light, but are responding to changes in nearby surrounding water pressure. As such, flatworms are essentially feeling their way around the reef. Yesterday, I observed a flatworm trying to cross over a section littered with tiny hydroids. The flatworm displayed some kind of reflex action that suggested that it might have received a sting from the hydroids – curling up and contracting its body suddenly when it came into contact with a hydroid – however, it persevered forward and would only re-orientate itself when it got “stung”. If it could actually “see” what it was walking into, it might not have had to feel it’s way though the hydroid maze. While most flatworms have a pair of eyes, some can have a whole bunch of eyes concentrated around their head. Freaky.

Marine flatworms are free-living predators, not parasites, unlike their flatworm relatives. Believe it or not, these simple animals actually have brains. Albeit a simple one. They do have a nervous system, unlike corals and jellyfish that have nerve nets. They also have a gut and a digestive system, however they respire through their skin and so don’t have a respiratory system.

Like flatworms, nudibranches also move around the reef with the aid of mucous. Those that live on soft sand tend to have large feet and move with the help of cilia, those mobile hairs like the flatworm. Other slender nudibranches move themselves forward by creating a wave motion through their body.

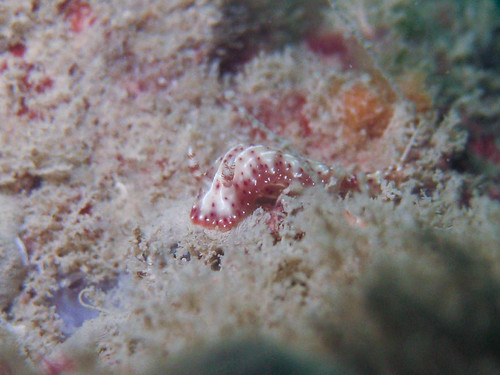

Some nudibranches that fancy creeping around hydroids or alga in a strong currents, have specialised pedal glands which produce a particularly sticky mucus so they retain a hold on their substrate, demonstrated by this Tambja nudibranch (above) that is perched on a hydroid. [1]

While traveling on mucous helps a nudibranch glide along with less effort, there is a drawback. Producing a mucous trail means nudibranches and sea slugs advertise their whereabouts at all times. Carnivorous species of sea slugs rely on this tell-tale trail to find their prey. It is also apparently useful in the peculiar ‘trailing’ behaviour that occurs in some species of nudibranch.

It’s not a sea slug, but it is sluggish – sea cucumbers also travel with the help of little feet called podia, or with muscular wave action like those slender nudibranches. Some species of sea cucumber are also able to swim, just like some nudibranches; the Bornella nudibranch is one example. Pelagic sea cucumbers also have developed webbing to aid them with swimming, so they no longer have a need for little feet or sluggish behavior.

For more photos from this dive, visit the Gallery.

Posted in

Posted in

content rss

content rss

COMMENTS