A Macro Look at Macro Life

June 6, 2013

June 6, 2013

If you love taking a closer look at life on the reef, you’ll love diving in Singapore. Though we do get surprised by some mega fauna every now and then – we’ve had schools of batfish, barracuda, and Silver moonies – to authentically enjoy Pulau Hantu’s reefs, we have to marvel at the impressive diversity of fauna that can fit within the palm of our hand. (Above: Goby on sponge)

The Doto nudibranch (above) is one of the many unique creatures that can be encountered at Pulau Hantu. It’s so strange and unusual that it doesn’t even have a name yet! To date, it’s known only as Doto sp. You won’t see it on the reefs per se, but if you take some time (sometimes, it might take a LONG time) to explore the depths of the sea bed, you might just be rewarded. Individuals might be the size of a rice grain or up to the size of your pinkie nail! There aren’t very many places in the world where this nudibranch can be easily found!

Rather than lamenting the limited underwater visibility, take advantage of it! (Oh my goodness, I’m beginning to sound like a motivational speaker?!) Seriously though, we are truly fortunate that there is macro life to be discovered in our local waters, otherwise there would be nothing for us to enjoy! Our city reefs may not seem like much at first, but it is evidently a prized habitat for many species of nudibranchs like the pair of Glossodoris atromarginata (above) that are on their way to starting a new generation on our reefs!

Other nudibranchs that are common on our reefs include (clockwise from top) Flabellina rubrolineata with its purple-coloured tips, Chromodoris cincta with its beautiful ruffled mantle, Jorunna funebris that is also known as the Oreo-cookie nudi because when it gets bigger its black dots become black discs, which reminds hungry divers of the cream-centered biscuit, and finally Chromodoris fidelis, also known as the Reliable chromodoris, for reasons unbeknownst to me!

Orange-spotted pipefish Corythoichthys ocellatus are relatives of the seahorse, and are relatively common on our reefs. In this photo it is evident that its habitat is heavily smothered by silt and algae. Perhaps such an environment is still suitable for species like this pipefish, as they quite favor coral rubble and the sandy reef bottom.

There are also several anemones around Pulau Hantu, some with residents like these False clown anemonefish Amphiprion ocellaris. Each anemone is “private” to each false-clown that lives in it: other false-clowns can be stung by the anemone, if they do not live in it. If a false-clown is removed from its anemone for a period longer than a few days, or weeks, and is then brought back again, it is stung by the anemone. However, it will return repeatedly, going through a stereotyped swimming dance, letting its ventral fins to be stung first, then its entire belly, until it acquires full immunity to the anemone’s sting and makes it its home.[1]

Other strange fish on our reefs are these Razorfish, which drift through the reef crest as if they were blades of seagrass carried by the currents!

As we lean in closer to the reef, we start to notice things we might otherwise miss should we casually drift by without making a closer inspection. These pretty Clavularia Glove Polyps, commonly referred to as Eight Tentacle Polyps, rely heavily on the products of their zooxanthellae but may also feed on phytoplankton and similarly sized microfauna in the water column. Like most corals, they are colonial animals with several individual polyps attached to a single piece of live rock. Clavularia is often stung and damaged by other aggressive corals, so you won’t find them growing right next to other corals, instead they prefer to have some space to themselves, like in the photo above.

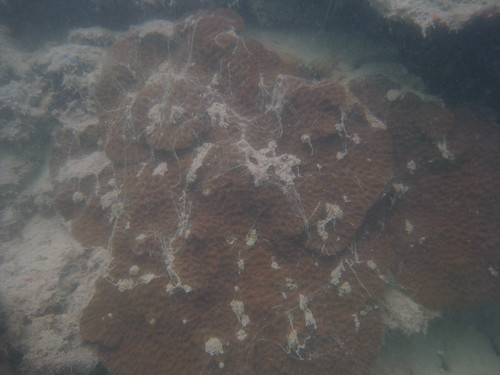

Apart from competing with other coral for space, corals also have to cope with relentlessly changing environmental conditions. When corals are stressed or sick, they produce a mucus to help them trap the particles that are causing them the irritation, kind of just like us! The mucus layer provides a important barrier between the coral epithelium, the thin outer layer of tissue on the coral surface, and the seawater environment, thus acting as a defense against a wide range of environmental stresses. [2]

Producing this mucus requires energy, which the coral desperately needs to help with its growth to remain competitive on the reef. We don’t yet know how much stress corals can take before the production of mucus begins to become counterproductive. But like any living thing, there is a finite amount of stress that can be tolerated. Coral reefs in Singapore receive a lot of pressure from the silt that constantly comes to settle on our reef and ocean floor.

It’s really important that we visit our reefs frequently and regularly, so that we can continue to monitor the changes that are occurring on the reef. There are so many questions that remain unanswered, and having people remain interested about local reefs helps us to keep our work going!

Posted in

Posted in

content rss

content rss

COMMENTS