Life on a Singapore Reef

February 2, 2016

February 2, 2016

While living on the reef may look like a cruise to the casual observer, life on the reef is in fact wrought with challenges! Little fish get eaten by big fish everyday. And big fish get eaten by even bigger fish. Whether it is day or night, animals on the reef have to balance looking for food or becoming food themselves. Even the coral that seems to just sit there has predators specially adapted to feed on them. The Copper-banded butterflyfish Chelmon rostratus (above) feeds on coral polyps, small invertebrates, and even anemones. It is one of the common butterflyfishes that can be encountered on our reefs., and form monogamous pairs. They are a precious part of our reef ecosystem and are an indicator species of reef health.

This pair of False-clown anemonefish Amphiprion ocellaris were rather territorial of their anemone. Usually they dart into the anemone when approached by a diver, but as you can see from the series of photos, the large female anemonefish came toward the camera several times. The last time I encountered such an aggressive female was when there was a nest of eggs within the anemone. I wonder if this pair also have a nest. I didn’t stay around to investigate as the fish made it clear that they didn’t want to be bothered.

Another one of three species of anemonefish that can be found in the reefs of Pulau Hantu include the Tomato-clown anemonefish Amphiprion frenatus.

Harlequin sweetlips Plectorhinchus chaetodonoides are also known as Clown sweetlips because the juveniles have spots and swim in a bizarre fashion.

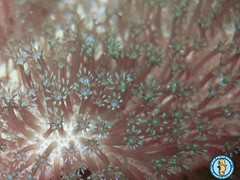

The brightly colored mantle and rows of minute eyes make this coral-boring scallop, Pedumsp., easily recognized on the reef. Some scallop swim free, either by a well developed foot or propelled along by a jet of water from their mantle cavity. But coral-boring scallop have a fragile shell and bury deep into coral recesses for protection against predators. (Top) Coral-boring scallop within a coral cavity. This one has bored into a Porites coral. (Above) Detail of coral-boring scallop showing its tentacles, eyes and mantle.

A pair of mating Hypselodoris bullocki.

These two were really tiny nudibranchs. No more than half a centimetre. The white one at the bottom has been identified as Goniodoridella sp., thanks to Chay Hoon! It goes to show that there is definitely more to the reef than meets the eye! It pays to move slowly along the reef and take your time to observe the patterns on the reef!

Sea-whip gobies Bryaninops are so called because they are a commensal on sea whips (gorgonian corals). They are cryptically coloured to help them blend into their host coral.

Another goby resting on a piece of broken coral on the reef.

A small school of razorfish drift along the shallow reef. I noticed that while the territorial Honeyhead damsel Dischistodus prosopotaenia was quick to chase off other fish from its territory, these razorfish could “float” right through it, and even swam right past the damsel fish. I wonder if the damsel fish realises these fish aren’t a threat to it, or if the disguise as blades of grass has fooled it too.

The nooks and crannies along the coral reef provide a lot of hiding opportunities for reef animals. Such as this Seagrass filefish Acreichthys tomentosum that has found a nice spot between a coral and a sponge.

There were many bright and beautiful hard and soft corals on the reef. Coral tissue is actually transparent. The bright colours we see are colourful photosynthetic microscopic algae called zooxanthellae that live within its tissue. The zooxanthellae have a symbiotic relationship with the coral animal. The coral gives the microscopic algae a place to live and grow, safe from predators, while the coral gets some food in return for the shelter it provides.

As with corals all over the world, Singapore reefs are threatened by the effects of increasing sea surface temperatures that are influenced by the El Niño event that has been forecasted to last through the first quarter of 2016. The NEA website reports that, “sea-surface temperatures (SST) continue to follow closely the patterns of the 1982-83 and 1997-98 El Niño events, which are among the strongest on records.” In 1998, sea temperatures around Pulau Hantu and St John’s Island were elevated by 1-2 degrees. 50-90% of all reef organisms in Singapore were affected, particularly the hard corals, soft corals and anemones. The bleaching effect extended to 6m, which is the lower growth depth limit for local coral growth. A study of the stressed colonies revealed that 10 out of 35 coral colonies died from the stress, and the genera Sinularia and Euphyllia were most affected. In the photo above, Flase-clown anemonefish swim amidst an anemone that has begun to bleach.

Coral bleaching occurs when the coral animal ejects the zooxanthellae as a response to stressful conditions, particularly when there is an increase in SST, thereby losing their colour and appearing white or bleached.

Zooxanthellae provide coral with up to 90% of their daily energy requirements through photosynthesis. During bleaching, corals can lose up to 90% of their zooxanthellae and the remaining zooxanthellae can lose up to 80% of its photosynthetic pigments. During this time, the coral would have to rely more on active feeding for nourishment. If the corals remained stressed for an extended period of time, they eventually die leaving behind the calcium carbonate exoskeleton.[1] In 1998, the biggest bleaching event in history led to the death of 16% of the world’s coral reefs.

We are very lucky to have these wonderful living reefs for us to explore and have fun in. These reefs are unique, and they are Singapore’s very own. But it may not always be here. Our reefs are threatened by development, climate change, and even unmanaged interaction and extraction activities. While some of the threats are hard for us to stop now, there are many other things we can do to help keep them around for our well-being and quality of life. By visiting and learning about our reefs, letting people know that you care about our reefs, and becoming involved as a volunteer with many of the coastal or marine protection organisations, we can help to keep our reefs around for as long as possible! To see all the photos from this dive, visit our gallery!

Posted in

Posted in

content rss

content rss

COMMENTS